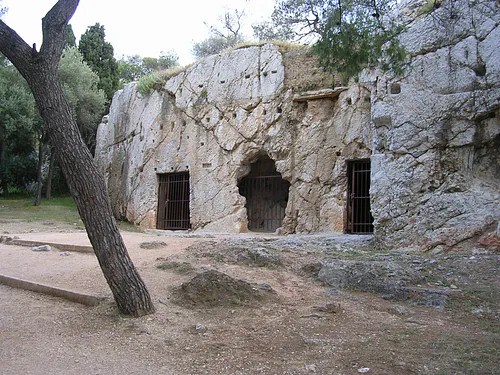

“The death sentence of Socrates was the legal consequence of asking politico-philosophic questions of his students, which resulted in the two accusations of moral corruption and impiety. At trial, the majority of the dikasts (male-citizen jurors chosen by lot) voted to convict him of the two charges; then, consistent with common legal practice voted to determine his punishment and agreed to a sentence of death to be executed by Socrates’s drinking a poisonous beverage of hemlock.”

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Trial_of_Socrates

SOCRATES FINAL SPEECH

http://www.worldfuturefund.org/Reports/Socrates/socrates.html#:~:text=DEATH%20AND%20FATE,end%20happened%20by%20mere%20chance."Some one will say: Yes, Socrates, but cannot you hold your tongue, and then you may go into a foreign city, and no one will interfere with you? Now I have great difficulty in making you understand my answer to this. For if I tell you that to do as you say would be a disobedience to the God, and therefore that I cannot hold my tongue, you will not believe that I am serious; and if I say again that daily to discourse about virtue, and of those other things about which you hear me examining myself and others, is the greatest good of man, and that the unexamined life is not worth living, you are still less likely to believe me. Yet I say what is true, although a thing of which it is hard for me to persuade you....

...Reflecting that I was really too honest a man to be a politician and live, I did not go where I could do no good to you or to myself; but where I could do the greatest good privately to every one of you, thither I went, and sought to persuade every man among you that he must look to himself, and seek virtue and wisdom before he looks to his private interests, and look to the state before he looks to the interests of the state; and that this should be the order which he observes in all his actions....

...The difficulty, my friends, is not to avoid death, but to avoid unrighteousness; for that runs faster than death. I am old and move slowly, and the slower runner has overtaken me, and my accusers are keen and quick, and the faster runner, who is unrighteousness, has overtaken them. And now I depart hence condemned by you to suffer the penalty of death,—they too go their ways condemned by the truth to suffer the penalty of villainy and wrong; and I must abide by my award—let them abide by theirs....

...And now, O men who have condemned me, I would fain prophesy to you; for I am about to die, and in the hour of death men are gifted with prophetic power. And I prophesy to you who are my murderers, that immediately after my departure punishment far heavier than you have inflicted on me will surely await you. Me you have killed because you wanted to escape the accuser, and not to give an account of your lives. But that will not be as you suppose: far otherwise. For I say that there will be more accusers of you than there are now; accusers whom hitherto I have restrained: and as they are younger they will be more inconsiderate with you, and you will be more offended at them.If you think that by killing men you can prevent some one from censuring your evil lives, you are mistaken; that is not a way of escape which is either possible or honourable; the easiest and the noblest way is not to be disabling others, but to be improving yourselves.This is the prophecy which I utter before my departure to the judges who have condemned me....

...What would not a man give if he might converse with Orpheus and Musaeus and Hesiod and Homer? Nay, if this be true, let me die again and again. I myself, too, shall have a wonderful interest in there meeting and conversing with Palamedes, and Ajax the son of Telamon, and any other ancient hero who has suffered death through an unjust judgment; and there will be no small pleasure, as I think, in comparing my own sufferings with theirs. Above all, I shall then be able to continue my search into true and false knowledge; as in this world, so also in the next; and I shall find out who is wise, and who pretends to be wise, and is not. What would not a man give, O judges, to be able to examine the leader of the great Trojan expedition; or Odysseus or Sisyphus, or numberless others, men and women too! What infinite delight would there be in conversing with them and asking them questions! In another world they do not put a man to death for asking questions: assuredly not. For besides being happier than we are, they will be immortal, if what is said is true....

...Wherefore, O judges, be of good cheer about death, and know of a certainty, that no evil can happen to a good man, either in life or after death. He and his are not neglected by the gods; nor has my own approaching end happened by mere chance. But I see clearly that the time had arrived when it was better for me to die and be released from trouble; wherefore the oracle gave no sign. For which reason, also, I am not angry with my condemners, or with my accusers; they have done me no harm, although they did not mean to do me any good; and for this I may gently blame them. Still I have a favour to ask of them. When my sons are grown up, I would ask you, O my friends, to punish them; and I would have you trouble them, as I have troubled you, if they seem to care about riches, or anything, more than about virtue; or if they pretend to be something when they are really nothing,—then reprove them, as I have reproved you, for not caring about that for which they ought to care, and thinking that they are something when they are really nothing. And if you do this, both I and my sons will have received justice at your hands....

-Plato

Last words…

“Go,”said he [= Socrates], “and do as I say.” Crito, when he heard this, signaled with a nod to the boy servant who was standing nearby, and the servant went in, remaining for some time, and then came out with the man who was going to administer the poison [pharmakon]. He was carrying a cup that contained it, ground into the drink. When Socrates saw the man he said: “You, my good man, since you are experienced in these matters, should tell me what needs to be done.” The man answered: “You need to drink it, that’s all. Then walk around until you feel a heaviness |117b in your legs. Then lie down. This way, the poison will do its thing.” While the man was saying this, he handed the cup to Socrates. And Socrates took it in a cheerful way, not flinching or getting pale or grimacing. Then looking at the man from beneath his brows, like a bull—that was the way he used to look at people—he said: “What do you say about my pouring a libation out of this cup to someone? Is it allowed or not?” The man answered: “What we grind is measured out, Socrates, as the right dose for drinking.” “I understand,” he said, |117c “but surely it is allowed and even proper to pray to the gods so that my transfer of dwelling [met-oikēsis] from this world [enthende] to that world [ekeîse] should be fortunate. So, that is what I too am now praying for. Let it be this way.” And, while he was saying this, he took the cup to his lips and, quite readily and cheerfully, he drank down the whole dose. Up to this point, most of us had been able to control fairly well our urge to let our tears flow; but now when we saw him drinking the poison, and then saw him finish the drink, we could no longer hold back, and, in my case, quite against my own will, my own tears were now pouring out in a flood. So, I covered my face and had a good cry. You see, I was not crying for him, |117d but at the thought of my own bad fortune in having lost such a comrade [hetairos]. Crito, even before me, found himself unable to hold back his tears: so he got up and moved away. And Apollodorus, who had been weeping all along, now started to cry in a loud voice, expressing his frustration. So, he made everyone else break down and cry—except for Socrates himself. And he said: “What are you all doing? I am so surprised at you. I had sent away the women mainly because I did not want them |117e to lose control in this way. You see, I have heard that a man should come to his end [teleutân] in a way that calls for measured speaking [euphēmeîn]. So, you must have composure [hēsukhiā], and you must endure.” When we heard that, we were ashamed, and held back our tears. He meanwhile was walking around until, as he said, his legs began to get heavy, and then he lay on his back—that is what the man had told him to do. Then that same man who had given him the poison [pharmakon] took hold of him, now and then checking on his feet and legs; and after a while he pressed his foot hard and asked him if he could feel it; and he said that he couldn’t; and then he pressed his shins, |118a and so on, moving further up, thus demonstrating for us that he was cold and stiff. Then he [= Socrates] took hold of his own feet and legs, saying that when the poison reaches his heart, then he will be gone. He was beginning to get cold around the abdomen. Then he uncovered his face, for he had covered himself up, and said— this was the last thing he uttered— “Crito, I owe the sacrifice of a rooster to Asklepios; will you pay that debt and not neglect to do so?” “I will make it so,” said Crito, “and, tell me, is there anything else?” When Crito asked this question, no answer came back anymore from Socrates. In a short while, he stirred. Then the man uncovered his face. His eyes were set in a dead stare. Seeing this, Crito closed his mouth and his eyes. Such was the end [teleutē], Echecrates, of our comrade [hetairos]. And we may say about him that he was in his time the best [aristos] of all men we ever encountered—and the most intelligent [phronimos] and most just [dikaios].”*

-Phaedo

Plato

(Translated by Gregory Nagy)

The Death of Socrates